Validity in research is essential for producing accurate, trustworthy, and meaningful results. It refers to how well a study measures what it is intended to measure and whether the results truly reflect the real-world situation being examined. Without validity, even well-designed studies can lead to misleading conclusions, wasted resources, and poor decision-making. Researchers must carefully plan their methods to ensure their findings are both reliable and valid. This includes choosing the right tools, avoiding bias, and clearly defining variables.

There are several types of validity—such as internal, external, construct, and content validity—each addressing a different aspect of the research process. Understanding these types helps researchers strengthen their studies and improve the impact of their work. This article will explore the different forms of validity, explain why they matter, and offer practical strategies to maintain high standards of research quality across various fields of study.

Types of Validity

Research validity encompasses several distinct categories, each addressing different aspects of study design and measurement. Understanding these types is crucial for designing robust studies and interpreting results accurately.

Internal Validity

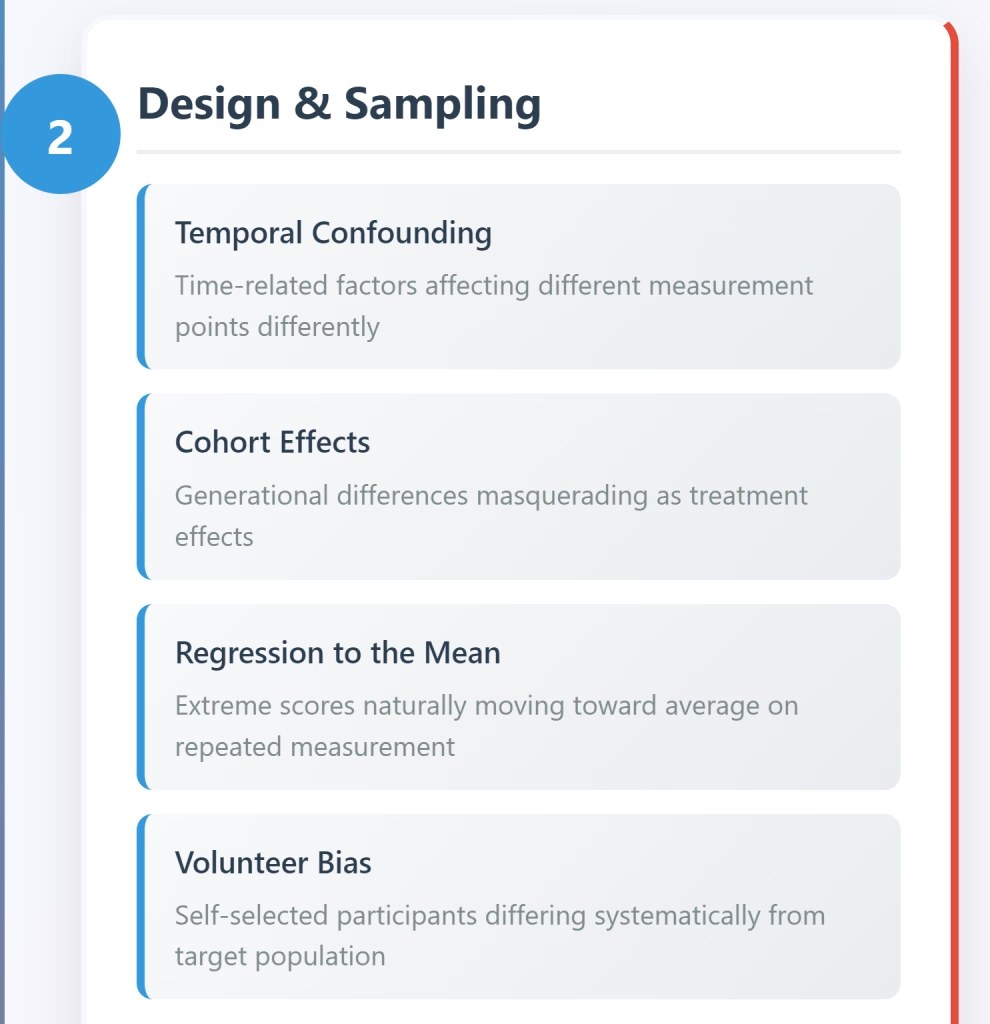

Internal validity refers to the degree to which a study can establish a causal relationship between variables. It asks whether the observed effects are truly due to the independent variable rather than other factors. Strong internal validity requires controlling for confounding variables, using appropriate randomization, and minimizing bias in data collection. Common threats include selection bias, history effects, maturation, and instrumentation changes.

External Validity

External validity concerns the generalizability of research findings beyond the specific study context. It examines whether results can be applied to different populations, settings, or time periods. Factors affecting external validity include the representativeness of the sample, the artificiality of the research environment, and the specificity of the intervention. Researchers must balance controlled conditions with real-world applicability.

Construct Validity

Construct validity evaluates whether a study’s operational definitions and measurements accurately represent the theoretical concepts being investigated. It ensures that instruments and procedures truly capture the intended constructs rather than measuring something else entirely. This type includes convergent validity (similar measures correlate) and discriminant validity (different constructs don’t correlate inappropriately).

Content Validity

Content validity assesses whether a measurement instrument adequately covers all aspects of the construct it claims to measure. Expert panels typically evaluate whether items or questions comprehensively represent the domain of interest. This is particularly important in educational testing, psychological assessments, and survey research where complete coverage of the topic is essential.

Criterion Validity

Criterion validity examines how well a measure correlates with established standards or outcomes. It includes concurrent validity (correlation with existing measures) and predictive validity (ability to forecast future outcomes). For example, a new aptitude test should correlate with established tests and predict future academic performance.

Face Validity

Face validity represents the most basic form, asking whether a measure appears to assess what it claims to measure. While important for participant acceptance and understanding, face validity alone is insufficient for scientific rigor. A measure can have high face validity but low actual validity, or vice versa.

Importance of Validity in Research

Scientific Credibility and Trust

Valid research builds trust in scientific findings and maintains the credibility of the research enterprise. When studies lack validity, they contribute to the replication crisis and erode public confidence in science. The scientific community relies on valid research to build cumulative knowledge, where each study contributes meaningfully to the broader understanding of phenomena.

Informed Decision-Making

Research findings directly influence policy decisions, clinical practices, and organizational strategies. Invalid research can lead to ineffective or harmful interventions. For instance, educational policies based on flawed studies may waste resources and harm student outcomes. Similarly, medical treatments validated through invalid research can endanger patient safety and delay the development of effective therapies.

Resource Optimization

Valid research ensures that limited resources—time, funding, and human effort—are used effectively. Invalid studies not only waste these resources but also create opportunity costs by preventing investment in more promising research directions. Funding agencies increasingly emphasize validity in their evaluation criteria to maximize the return on research investments.

Ethical Responsibility

Researchers have an ethical obligation to conduct valid studies, particularly when involving human participants. Invalid research violates the principle of beneficence by potentially exposing participants to risks without generating meaningful benefits. It also breaches the trust that participants place in the research process.

Advancement of Knowledge

Valid research contributes to the systematic advancement of knowledge within disciplines. It allows for meaningful comparisons across studies, enables meta-analyses, and supports the development of theories and models. Invalid research creates noise in the scientific literature and can lead entire fields down unproductive paths.

Practical Applications

The practical value of research depends entirely on its validity. Interventions, treatments, and solutions derived from invalid research are unlikely to work in real-world settings. This is particularly critical in applied fields like medicine, education, and engineering, where research directly translates into practice.

How to Ensure Validity in Research

Research Design Phase

Careful Planning and Literature Review

Conduct thorough literature reviews to understand existing knowledge and identify gaps. This helps refine research questions and ensures that constructs are well-defined and measurable. Clear operational definitions prevent construct validity issues later in the study.

Randomization and Control Groups

Use random assignment when possible to minimize selection bias and enhance internal validity. Implement appropriate control groups to isolate the effects of the independent variable. Consider using randomized controlled trials as the gold standard for establishing causal relationships.

Sample Selection and Size

Choose representative samples that reflect the target population to improve external validity. Calculate appropriate sample sizes using power analyses to ensure adequate statistical power. Consider stratified sampling when studying diverse populations to maintain representativeness.

Measurement and Instrumentation

Validated Instruments

Use established, validated measurement tools whenever possible. If creating new instruments, conduct pilot testing and validation studies. Ensure instruments have demonstrated reliability and validity in similar populations and contexts.

Multiple Measurement Methods

Employ triangulation by using multiple methods to measure the same construct. This approach strengthens construct validity by confirming results across different measurement approaches. Combine quantitative and qualitative methods when appropriate.

Pre-testing and Calibration

Conduct pilot studies to identify potential problems with instruments or procedures. Calibrate equipment regularly and train data collectors thoroughly to minimize measurement errors that threaten internal validity.

Data Collection Strategies

Standardized Procedures

Develop detailed protocols for data collection to ensure consistency across participants and settings. Train all research staff on standardized procedures to minimize variability that could compromise validity.

Blinding and Masking

Implement single or double-blinding procedures when feasible to reduce bias. Keep participants and researchers unaware of group assignments or study hypotheses to prevent expectancy effects.

Environmental Controls

Control for environmental factors that might influence results. Maintain consistent conditions across data collection sessions and document any deviations from standard procedures.

Statistical and Analytical Approaches

Appropriate Statistical Tests

Select statistical methods that match your data type and research design. Ensure assumptions of statistical tests are met, and use robust alternatives when assumptions are violated.

Control for Confounding Variables

Identify potential confounding variables and control for them statistically or through design. Use techniques like matching, stratification, or statistical covarying to isolate the effects of interest.

Sensitivity Analyses

Conduct sensitivity analyses to test how robust your findings are to different analytical approaches or assumptions. This helps establish the stability of your conclusions.

Quality Assurance Measures

Peer Review and Collaboration

Engage colleagues in reviewing research designs and methods before implementation. Collaborative oversight helps identify potential validity threats that individual researchers might overlook.

Documentation and Audit Trails

Maintain detailed records of all procedures, decisions, and modifications throughout the study. This documentation supports transparency and allows for quality checks.

Replication and Validation Studies

Plan for replication studies or conduct internal replications when possible. Cross-validate findings across different samples or time periods to strengthen external validity.

Post-Data Collection Validation

Data Quality Checks

Implement systematic data cleaning procedures to identify and address errors, outliers, or missing data patterns that might compromise validity.

Manipulation Checks

Verify that experimental manipulations worked as intended. Include manipulation checks in experimental designs to confirm that participants perceived and responded to interventions appropriately.

Member Checking

In qualitative research, return findings to participants for verification and feedback. This process helps ensure that interpretations accurately reflect participants’ experiences and perspectives.

Research Validity Threats Throughout the Research Process

Common Mistakes That Threaten Validity

Design-Related Mistakes

Inadequate Sample Sizes

Underpowered studies fail to detect true effects, leading to false negative results and threatening statistical conclusion validity. Many researchers underestimate the sample size needed for their analyses, particularly when studying small effect sizes or using complex statistical models.

Selection Bias

Failing to use random sampling or random assignment creates systematic differences between groups that confound results. Self-selection into treatment groups, volunteer bias, and convenience sampling all threaten both internal and external validity.

Confounding Variables

Overlooking important variables that influence both the independent and dependent variables can create spurious relationships. Common confounders include socioeconomic status, age, education level, and baseline differences between groups.

Poor Operational Definitions

Vague or inconsistent definitions of key constructs make it impossible to measure them accurately. This fundamental error undermines construct validity and makes replication difficult.

Measurement Errors

Using Unvalidated Instruments

Researchers sometimes create their own measures without proper validation, assuming face validity is sufficient. This approach often results in instruments that don’t actually measure the intended constructs.

Single Method Bias

Relying on only one measurement method makes studies vulnerable to method-specific errors. For example, using only self-report measures can introduce social desirability bias and common method variance.

Instrumentation Changes

Modifying measurement procedures, criteria, or instruments during data collection creates inconsistencies that threaten internal validity. Even minor changes can systematically bias results.

Scale Mismatches

Using measurement scales inappropriate for the research question or population can produce meaningless results. This includes using adult measures with children or culturally inappropriate instruments.

Data Collection Issues

Inconsistent Procedures

Varying data collection procedures across participants, sites, or time periods introduces unwanted variability that can mask true effects or create false ones. Lack of standardization is particularly problematic in multi-site studies.

Researcher Bias

Allowing data collectors’ expectations or knowledge of group assignments to influence their interactions with participants or their recording of observations introduces systematic bias.

Attrition and Missing Data

High dropout rates or systematic patterns of missing data can severely compromise validity. Differential attrition between groups is particularly problematic for internal validity.

Environmental Contamination

Failing to control for environmental factors that might influence results across different conditions or time periods. This includes seasonal effects, historical events, or changes in organizational climate.

Statistical and Analytical Errors

Inappropriate Statistical Tests

Using statistical procedures that don’t match the data structure or research design can lead to incorrect conclusions. Common errors include treating ordinal data as interval or ignoring clustered data structures.

Multiple Comparisons

Conducting numerous statistical tests without appropriate corrections inflates the risk of Type I errors, leading to false positive findings that don’t replicate.

Post-hoc Hypothesizing

Developing hypotheses after examining the data (HARKing – Hypothesizing After Results are Known) inflates the apparent significance of findings and misleads readers about the study’s confirmatory nature.

Ignoring Assumptions

Failing to check or address violations of statistical assumptions can invalidate results. This includes assumptions about normality, independence, and homogeneity of variance.

Interpretation and Reporting Mistakes

Overgeneralization

Extending findings beyond the scope of the study population, setting, or conditions without adequate justification threatens external validity. This is particularly common when generalizing from laboratory to real-world settings.

Causal Claims from Correlational Data

Drawing causal conclusions from correlational or observational studies without appropriate design features or analytical techniques to support causal inference.

Cherry-picking Results

Selectively reporting only significant findings while ignoring non-significant results creates publication bias and distorts the literature. This practice threatens the cumulative validity of research fields.

Inadequate Effect Size Reporting

Focusing solely on statistical significance while ignoring practical significance can mislead readers about the real-world importance of findings.

Prevention Strategies

Systematic Planning

Develop comprehensive research protocols that address potential validity threats before data collection begins. Use checklists and guidelines specific to your research design.

Pilot Testing

Conduct thorough pilot studies to identify and address problems before full implementation. Test all procedures, instruments, and analytical approaches on smaller samples first.

External Review

Seek feedback from colleagues, mentors, and subject matter experts throughout the research process. Fresh perspectives often identify validity threats that researchers miss.

Transparent Reporting

Document all procedures, decisions, and modifications clearly. Follow established reporting guidelines for your research design to ensure readers can properly evaluate validity.

FAQs

How to tell if a research paper is valid?

Check if the study has a clear research design, uses reliable and appropriate methods, controls for bias, and the results align logically with the conclusions. Peer review and replication also support validity.

How to test for validity?

Use techniques like pilot testing, comparing with established measures (criterion validity), expert reviews (content validity), and statistical analysis to confirm that tools measure what they claim to measure.

What is the difference between validity and accuracy?

Validity refers to whether a method truly measures what it is intended to measure, while accuracy refers to how close the results are to the true or accepted value. Validity is broader and includes accuracy as part of it.