A thematic essay is a type of writing that focuses on exploring a central theme or idea and showing how it connects to various examples, events, or texts. Unlike a simple summary, a thematic essay requires the writer to think critically and demonstrate how evidence supports the chosen theme. This kind of essay is often used in academic settings because it encourages students to analyze patterns, draw conclusions, and present ideas in a clear, structured way.

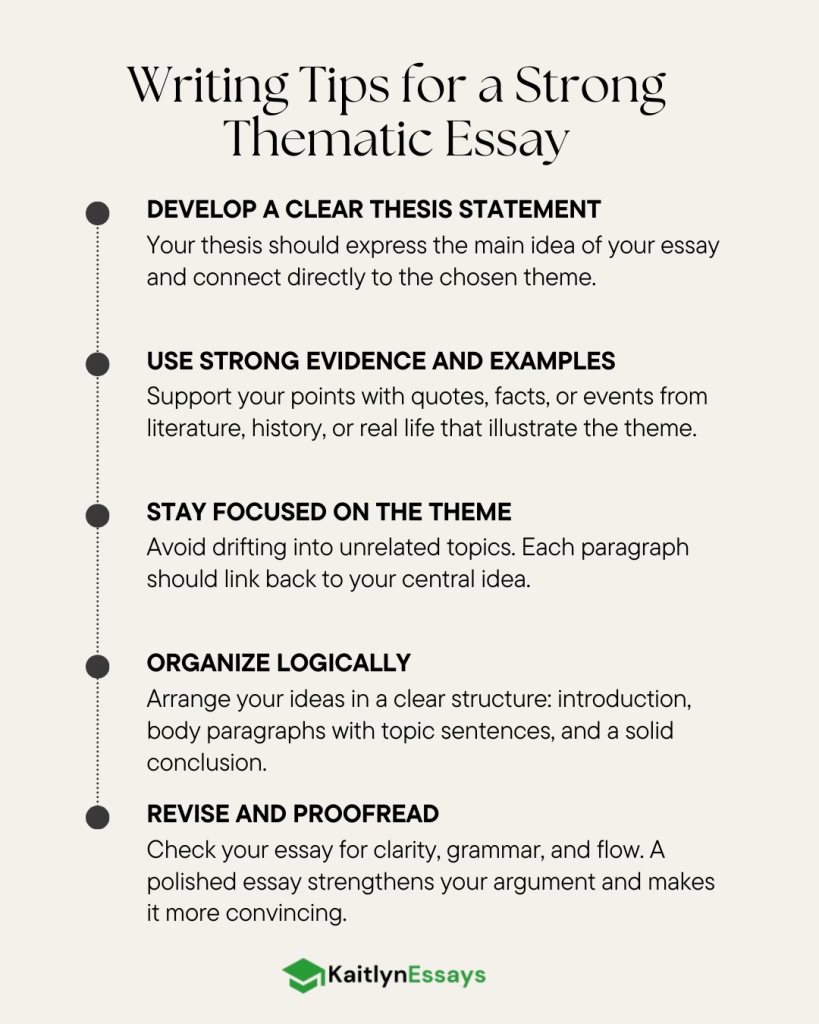

Writing a strong thematic essay involves identifying a central message, creating a well-organized thesis, and supporting it with relevant details or historical facts. It also requires careful organization so that each part of the essay connects back to the main theme. By practicing this type of writing, students can strengthen their analytical and communication skills while gaining a deeper understanding of the subject matter.

Key Features of a Thematic Essay

A thematic essay is built around a central theme or main idea that serves as the organizing principle for the entire piece. The key features include:

Central Theme Focus: The essay revolves around one overarching theme that connects all parts of the analysis. This theme acts as a lens through which all evidence and arguments are examined.

Evidence Integration: Multiple sources, examples, or pieces of evidence are woven together to support the central theme. Rather than analyzing sources separately, a thematic essay shows how different materials relate to and illuminate the main theme.

Analytical Structure: The organization follows the theme’s logical development rather than chronological order or source-by-source analysis. Each paragraph or section advances understanding of the central theme.

Synthesis and Connection: The essay demonstrates relationships between different ideas, events, or texts by showing how they all connect to the main theme. This requires higher-order thinking skills to identify patterns and make meaningful connections.

Interpretive Argument: Beyond simply describing the theme, these essays present an argument about the theme’s significance, meaning, or implications.

Differences from Other Essay Types

Thematic essays differ from other common essay formats in several important ways:

Versus Comparative Essays: While comparative essays focus on similarities and differences between two or more subjects, thematic essays use comparison only as a tool to illuminate a central theme that transcends the individual subjects.

Versus Chronological/Narrative Essays: Rather than following a timeline or telling a story in sequence, thematic essays organize information around conceptual connections to the main theme.

Versus Analytical Essays of Single Works: Unlike essays that analyze one text or source in depth, thematic essays draw from multiple sources to explore how a theme manifests across different contexts.

Versus Expository Essays: While expository essays explain or inform about a topic, thematic essays argue for a particular interpretation or understanding of how a theme operates across various materials.

Versus Persuasive Essays: Although thematic essays present arguments, they focus on interpreting and analyzing thematic connections rather than persuading readers to take a specific action or adopt a particular viewpoint.

Common Contexts and Applications

Thematic essays appear frequently across educational and professional contexts:

Academic Coursework: Literature classes often assign thematic essays to analyze recurring motifs across multiple works by different authors. History courses use them to explore themes like revolution, social change, or cultural conflict across different time periods or regions. Philosophy and social science courses employ thematic essays to examine concepts like justice, identity, or power across various theoretical frameworks.

Standardized Testing: Many state exams and standardized tests include thematic essay prompts, particularly in English Language Arts and Social Studies. The New York State Regents exams are well-known for their thematic essay questions that require students to analyze historical themes using specific examples from their studies.

Advanced Placement Exams: AP courses frequently use thematic essay formats, especially in AP Literature, AP History, and AP Art History, where students must demonstrate their ability to synthesize knowledge around central themes.

Research and Scholarship: Graduate-level research often employs thematic analysis when examining how particular concepts or ideas manifest across different texts, time periods, or cultural contexts. Doctoral dissertations frequently organize literature reviews thematically rather than chronologically.

Professional Writing: In fields like education, social work, and policy analysis, thematic essays help organize complex information around key concepts to inform decision-making and program development.

Choosing a Theme

Understanding What Makes a Strong Theme

Selecting an effective theme is crucial for writing a successful thematic essay. A strong theme serves as the foundation that will support your entire analysis and argument.

Broad Enough for Multiple Examples: Your theme should be sufficiently expansive to allow you to draw evidence from various sources, time periods, or contexts. Themes like “the struggle for power,” “the impact of technology on society,” or “individual versus community” offer rich possibilities for exploration across different materials.

Specific Enough for Focus: While breadth is important, your theme must also be narrow enough to allow for detailed analysis within your essay’s scope. “Love” might be too broad, but “the destructive nature of obsessive love” provides clearer boundaries for your analysis.

Intellectually Substantial: Choose themes that offer depth and complexity rather than surface-level observations. Strong themes typically involve conflicts, tensions, or paradoxes that invite thoughtful analysis and interpretation.

Sources of Theme Inspiration

From Your Course Materials: Review your readings, lectures, and class discussions for recurring concepts or ideas that appear across multiple texts or historical periods. Pay attention to patterns your instructor emphasizes or questions that keep arising in class.

From Assignment Guidelines: Many thematic essay prompts provide theme options or suggest general areas to explore. Use these as starting points, but consider how you can bring your own interpretive angle to the suggested themes.

From Current Events and Personal Interests: Themes that connect to contemporary issues or your own experiences often produce more engaging and insightful essays. Consider how historical or literary themes relate to modern situations.

From Conflicts and Contradictions: Look for tensions within your source materials—places where different characters, historical figures, or authors take opposing positions on important issues. These conflicts often reveal rich thematic possibilities.

Evaluating Theme Viability

Evidence Availability: Before committing to a theme, ensure you have access to sufficient evidence from your required sources. Can you find at least three strong examples that clearly relate to your chosen theme?

Analytical Potential: Ask yourself whether your theme allows for deeper analysis beyond simple description. Strong themes enable you to explore cause and effect, examine motivations, or reveal hidden connections between seemingly disparate materials.

Personal Engagement: Choose a theme that genuinely interests you. Your enthusiasm for the topic will show in your writing and motivate you through the research and drafting process.

Originality Within Bounds: While you don’t need to choose an entirely unique theme, consider how you can bring a fresh perspective to familiar topics. What specific angle or interpretation can you offer?

Common Theme Categories

Universal Human Experiences: Themes related to love, death, coming of age, the search for identity, or the struggle for survival appear across cultures and time periods, offering rich material for analysis.

Social and Political Issues: Power dynamics, social justice, conflict resolution, the role of leadership, or the tension between individual rights and collective needs provide substantial analytical opportunities.

Cultural and Philosophical Concepts: The nature of heroism, the meaning of progress, the relationship between tradition and change, or the role of fate versus free will offer sophisticated thematic possibilities.

Moral and Ethical Questions: The nature of good and evil, the complexity of moral choices, the consequences of betrayal, or the price of ambition allow for nuanced analysis of character motivations and societal values.

Refining Your Chosen Theme

Develop a Clear Theme Statement: Once you’ve selected a general thematic area, craft a specific statement that captures your particular interpretation. Instead of “war,” you might focus on “how war reveals both the worst and best aspects of human nature.”

Test Against Your Evidence: Ensure your refined theme statement can be supported by concrete examples from your source materials. If you’re struggling to find evidence, consider adjusting your theme rather than forcing connections.

Consider Multiple Perspectives: Strong themes often involve complexity and contradiction. Think about how different sources might present varying viewpoints on your theme, and how these differences contribute to a richer understanding.

Plan for Development: Visualize how your theme can be developed across multiple paragraphs or sections. Can you identify sub-themes or different aspects of your main theme that will allow for organized, coherent development?

Structure of a Thematic Essay

Overall Organization Principles

The structure of a thematic essay differs from other essay formats because it prioritizes thematic coherence over chronological order or source-by-source analysis. Every element of the essay should advance understanding of your central theme.

Theme-Driven Organization: Rather than organizing by time periods, individual works, or authors, structure your essay around different aspects, manifestations, or implications of your central theme. Each major section should explore a distinct dimension of the theme while maintaining clear connections to the overall argument.

Logical Progression: Arrange your main points in an order that builds understanding progressively. You might move from simple to complex manifestations of the theme, from historical to contemporary examples, or from individual to societal implications.

Integrated Evidence: Unlike essays that analyze sources separately, thematic essays weave evidence from multiple sources throughout each section to demonstrate how different materials illuminate the same thematic concept.

Introduction Structure

Hook with Thematic Relevance: Begin with an engaging opening that introduces your theme’s significance. This might be a thought-provoking question, a striking contradiction, or a compelling observation that highlights why your theme matters.

Context and Background: Provide necessary background information about your sources, time periods, or concepts, but only include details that directly relate to your thematic analysis. Avoid lengthy plot summaries or historical overviews that don’t advance your thematic argument.

Clear Thesis Statement: Present a specific, arguable thesis that articulates your interpretation of how the theme operates across your chosen materials. Your thesis should go beyond simply stating that the theme exists to argue for a particular understanding of its significance, patterns, or implications.

Preview of Structure: Briefly outline the main aspects of your theme that you’ll explore, giving readers a roadmap for your analysis without revealing all your conclusions.

Body Paragraph Framework

Thematic Topic Sentences: Begin each body paragraph with a topic sentence that identifies a specific aspect or manifestation of your central theme. This sentence should clearly connect to your thesis while introducing the particular angle you’ll examine in that section.

Multi-Source Integration: Within each paragraph, draw evidence from multiple sources to demonstrate how your theme manifests across different contexts. Rather than discussing each source separately, weave them together to show thematic connections and variations.

Analytical Development: Move beyond summary to analyze why your evidence supports your thematic interpretation. Explain the significance of patterns, contradictions, or variations you observe across different sources.

Transitional Connections: End each paragraph by connecting your analysis back to your central theme and preparing readers for the next aspect you’ll explore.

Methods for Organizing Body Sections

Chronological Thematic Development: While not strictly chronological, you might organize sections to show how your theme evolves or changes over time, demonstrating historical progression or development of ideas.

Comparative Thematic Analysis: Structure sections around different ways your theme manifests, comparing and contrasting how various sources treat the same thematic concept.

Cause and Effect Thematic Exploration: Organize around the causes that give rise to your theme and the effects or consequences that result from it, showing thematic relationships across your sources.

Problem and Solution Thematic Framework: Structure around how your sources identify thematic problems and propose or demonstrate various solutions or responses.

Evidence Integration Strategies

Balanced Source Usage: Ensure you’re drawing relatively equally from all required sources throughout your essay rather than relying heavily on some while neglecting others.

Specific Examples with Analysis: Include concrete details, quotes, or specific incidents from your sources, but always follow with analysis that explains how these examples illuminate your theme.

Synthesis Over Summary: Focus on showing connections and patterns across sources rather than simply describing what happens in each source independently.

Varied Evidence Types: Use different types of evidence—dialogue, character actions, historical events, statistical data, or symbolic elements—to demonstrate your theme’s complexity and breadth.

Advanced Structural Techniques

Thematic Layering: Develop your theme by exploring it at different levels—personal, social, cultural, or universal—showing how the same theme operates across various scales of human experience.

Dialectical Development: Structure your analysis around tensions or contradictions within your theme, showing how opposing forces or conflicting perspectives contribute to a more complex understanding.

Recursive Development: Return to key thematic concepts throughout your essay with increasing sophistication, building deeper understanding through repeated examination from different angles.

Conclusion Structure

Thematic Synthesis: Bring together the various aspects of your theme you’ve explored, showing how they combine to create a comprehensive understanding of your central concept.

Broader Implications: Discuss what your thematic analysis reveals about larger questions—human nature, society, historical patterns, or universal truths.

Contemporary Relevance: Connect your thematic insights to current issues or ongoing relevance, showing why understanding this theme matters today.

Avoid Simple Summary: Rather than merely restating your main points, demonstrate how your analysis has deepened understanding of your theme’s complexity and significance.

Example of a Thematic Essay

The Struggle Between Individual Identity and Social Conformity: A Thematic Analysis

Introduction

Throughout human history, individuals have faced the fundamental tension between maintaining their personal identity and conforming to societal expectations. This conflict between individual desires and social pressures appears repeatedly across literature, philosophy, and historical movements, revealing the complex relationship between personal freedom and collective harmony. By examining Henry David Thoreau’s “Civil Disobedience,” the protagonist Winston Smith in George Orwell’s 1984, and the historical example of the American Civil Rights Movement, we can see that while society often demands conformity to maintain order, true progress and human dignity require individuals who are willing to challenge unjust social norms, even at great personal cost. This tension between individual conscience and social conformity ultimately reveals that authentic human progress depends on the courage of individuals to resist oppressive social forces while working toward a more just collective future.

The Individual’s Moral Obligation to Resist Unjust Authority

The theme of individual versus society first manifests in the moral obligation to resist unjust laws and social practices. Thoreau’s “Civil Disobedience” provides a philosophical framework for this resistance, arguing that individuals must follow their conscience rather than blindly obey unjust laws. When Thoreau writes, “Under a government which imprisons any unjustly, the true place for a just man is also a prison,” he articulates the principle that moral individuals cannot remain passive when society perpetuates injustice. His own night in jail for refusing to pay taxes that supported slavery demonstrates how individual resistance to social norms requires personal sacrifice.

This same principle appears in Orwell’s 1984, where Winston Smith’s rebellion against the totalitarian Party represents the individual’s struggle to maintain authentic thought in a society that demands complete conformity. Winston’s secret diary writing and his affair with Julia are acts of individual assertion against a social system that seeks to eliminate all personal identity. His declaration that “Freedom is the freedom to say that two plus two make four” reveals how society’s control extends even to individual perception of reality. Unlike Thoreau’s principled civil disobedience, Winston’s resistance is more desperate and ultimately tragic, showing how totalitarian societies can crush individual spirit more completely than democratic ones.

The Civil Rights Movement provides historical validation of both Thoreau’s philosophy and Orwell’s warnings. Leaders like Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, and countless unnamed activists chose individual action over social conformity, knowing they would face imprisonment, violence, and social ostracism. King’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail” directly echoes Thoreau’s argument about the moral necessity of breaking unjust laws, writing that “one has not only a legal but a moral responsibility to disobey unjust laws.” Their individual acts of resistance challenged a social system that maintained racial segregation and inequality, demonstrating how personal courage can initiate broader social transformation.

The Price of Individual Resistance and Social Rejection

The conflict between individual and society inevitably involves significant personal costs for those who choose resistance over conformity. Thoreau’s voluntary simplicity at Walden Pond and his willingness to face imprisonment show how individual authenticity often requires rejecting society’s material values and accepting isolation. His experiment in simple living was partly a rejection of a society he saw as corrupted by materialism and injustice, yet this choice meant accepting a degree of social alienation and economic insecurity.

Winston Smith’s fate in 1984 represents the extreme consequences of individual resistance in totalitarian societies. His capture, torture, and eventual psychological destruction in Room 101 demonstrate how oppressive societies can eliminate not just individual action but individual thought itself. The Party’s ability to make Winston betray Julia and genuinely believe that “two plus two equals five” shows that some social systems are designed to completely obliterate individual identity. Winston’s final state—loving Big Brother—represents the ultimate victory of society over the individual, a cautionary vision of what happens when collective power becomes absolute.

The participants in the Civil Rights Movement faced real and immediate consequences that fell between Thoreau’s voluntary sacrifices and Winston’s total destruction. Civil rights activists endured economic boycotts, police violence, imprisonment, and sometimes death for challenging social norms. The children who integrated schools faced daily harassment and threats, while their parents often lost jobs and faced social ostracism. Yet unlike Winston Smith, these individuals maintained their sense of purpose and identity even while suffering social punishment, suggesting that democratic societies, despite their flaws, leave more room for individual dignity than totalitarian ones.

The Transformative Power of Individual Action on Social Progress

Despite the costs, individual resistance to unjust social norms proves essential for human progress and social evolution. Thoreau’s ideas about civil disobedience influenced generations of social reformers, showing how one individual’s principled stance can eventually transform broader social consciousness. His night in jail became a symbol of moral integrity that inspired later movements for social justice. His writing demonstrates how individual reflection and resistance can produce ideas that outlive their original context and continue to challenge future societies.

Even Winston Smith’s failed rebellion serves a purpose in Orwell’s narrative by illustrating the human capacity for individual thought and resistance, even under the most oppressive conditions. Although Winston is ultimately defeated, his initial ability to think independently and love authentically represents something essential about human nature that totalitarian societies seek to destroy but can never completely eliminate. His temporary success in maintaining individual identity, even in the face of overwhelming social pressure, suggests that the human spirit contains an irreducible element of individuality.

The Civil Rights Movement provides the most compelling example of how individual resistance can transform society. The collective impact of individual acts of courage—Rosa Parks refusing to give up her bus seat, Ruby Bridges walking into an all-white school, countless individuals participating in sit-ins and freedom rides—eventually dismantled legal segregation and changed American social norms. These individual actions created a momentum that forced society to confront its contradictions and move toward greater justice. The movement shows how individual resistance, when it connects with others sharing similar values, can reshape social structures and create new possibilities for human freedom and dignity.

The Complex Relationship Between Individual Freedom and Collective Responsibility

The tension between individual and society ultimately reveals that both personal freedom and collective cooperation are necessary for human flourishing, but achieving balance requires ongoing negotiation and occasional conflict. Thoreau’s experiment at Walden demonstrates both the value and the limitations of individual withdrawal from society. While his solitude allowed for deep reflection and authentic living, his most influential contributions came through his engagement with social issues like slavery and the Mexican-American War. His philosophy suggests that individuals need periodic separation from society to develop authentic values, but must eventually return to social engagement to make their insights meaningful.

Orwell’s 1984 warns that societies can become so oppressive that individual identity becomes impossible, but it also suggests that some form of collective organization is necessary for human civilization. The Party’s totalitarian control represents the extreme of collective power, but the alternative Orwell implies is not pure individualism but rather a society that balances collective needs with respect for individual dignity and freedom of thought.

The Civil Rights Movement demonstrates how individual conscience and collective action can work together to create positive social change. The movement required both individual courage and collective organization, showing that effective resistance to unjust social norms often depends on individuals who are willing to sacrifice personal comfort for broader principles while working within communities that share their values and goals.

Conclusion

The thematic exploration of individual versus society across these diverse sources reveals that human progress depends on maintaining productive tension between personal authenticity and collective responsibility. While society provides the structure and cooperation necessary for civilization, it can also become oppressive when it demands complete conformity at the expense of individual conscience and dignity. Thoreau’s philosophical framework, Winston Smith’s tragic resistance, and the Civil Rights Movement’s transformative success all demonstrate that individuals must sometimes challenge social norms to prevent society from stagnating or becoming unjust.

This theme remains critically relevant in contemporary society, where individuals continue to face pressure to conform to social expectations while grappling with questions of personal authenticity and moral responsibility. Whether confronting issues of political dissent, social media conformity, or institutional injustice, modern individuals must navigate the same fundamental tension between personal conviction and social belonging that Thoreau, Winston Smith, and civil rights activists faced in their respective contexts.

The healthiest societies are those that create space for individual difference and dissent while maintaining enough collective cohesion to address shared challenges and protect vulnerable members. The ongoing negotiation between individual freedom and collective responsibility requires citizens who are willing to think independently, act courageously, and engage thoughtfully with both personal conscience and community needs. This balance cannot be achieved once and maintained permanently, but must be continually renewed through the active participation of individuals who understand that authentic personal identity and just social structures depend on each other for their continued existence.

FAQs

How many paragraphs is a thematic essay?

Usually 5 paragraphs: an introduction, 3 body paragraphs, and a conclusion.

How to write an introduction paragraph for a thematic essay?

Start with a hook, give background on the theme, and end with a clear thesis statement.

What is an example of a thesis statement?

“Friendship is a powerful theme in literature because it highlights loyalty, trust, and personal growth.”